Why is my Jaw Popping, Cracking, Clicking and Locking? And How Can I Stop It?

An exploration into disc displacement and crepitus

There is not much of a standard for defining TMJ (Temporomandibular Joint) Disorders. But there's no doubt that one of the most common symptoms related to jaw dysfunction are noises emanating from the TMJ. Across studies, estimates range from 30-60% of patients experience these symptoms. In this article, we explore the anatomy of the TMJ in order to explain where those noises come from, what causes account for their development - because the first step in treating your TMD is understanding it.

The Anatomy of the TMJ

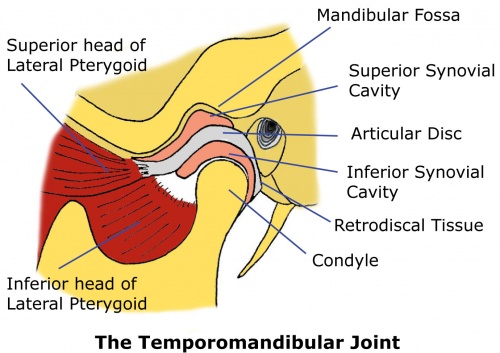

Don't worry if this looks confusing, we're going to go over everything you need to know right now. And as you continue reading, always feel free to look back at this section to remind yourself of what's what.

First let's take a look at the Condyle. This is simply the head of your mandible (the lower jaw bone), and is the part that rotates and slides around as you open and close your jaw.

Next, let's look at the other boney component of the TMJ - the temporal bone - which is a part of your skull. In the image above, the Mandibular Fossa is highlighted, which is simply the concave part of that bone that acts as the sort of inverse for the Condyle.

Between the two bones sits the Articular Disc which is a critical component in all this, so don't forget it. Its function is to distribute the forces in the joint across a larger area (to decrease pressure) and therefore prevent damage that can come from bone on bone contact.

However in a normal functional joint, the disc isn't simply sandwiched by the bones. Between all those moving parts exist just a bit of space that is filled with Synovial Fluid, which helps lubricate the joint and limit friction between the joint components during movement. This area of fluid is marked as the Synovial Cavities in the above image.

Next comes the Lateral Pterygoid muscle which comes with an upper and lower "head." There are a lot of muscles that play into TMD pain, but this one specifically is one of the most pesky and unknown to those first diagnosed with TMJ Disorder.

On the back side of the joint, right behind where the condyle sits is the Retrodiscal Tissue which is full of blood vessels and nerves.

And finally, there is a large network of ligaments surrounding the joint that are all named super sciency things. I'm not going to get too in depth on naming every single one, but don't think that's because they're not important. These ligaments play a critical role in the passive stability of the joint. Passive stability means that even when all muscles are relaxed, your joint remains positioned correctly. They're not, however, as elastic as muscles, which means that once they're stretched, they don't spring back to their original position.

This fact is actually really relevant to the topic of jaw clicking/popping, and I'll explain why soon. But it's also important in many other symptoms that won't be touched on in this article. For example, a lot of TMD patients have ear pain and tinnitus. The main explanation for this relates to a small ligament between the TMJ and the ear canal structure, in which damage to the ligament can cause damage to the ear canal structure.

What is Disc Displacement? It’s What Causes Clicking/Popping!

If you have a popping jaw, you’ll notice that you have 2 sounds: one as you open your mouth, and another as you close it. As I stated earlier, the big player when it comes to these TMJ noises is the articular disc.

If you scroll back up to the anatomical diagram, you’ll see that in a healthy TMJ, the articular disc sits right between the condyle and the fossa. But for many people with TMJ Disorder, the disc actually sits a little in FRONT of the condyle (or if you’re looking at the diagram, towards the left). This is called Disc Displacement. So what?

Well the articular disc is actually a special shape that allows the condyle to snugly sit within it. But wait, if the disc normally sits in front of the condyle, then how can it snugly fit inside? Well exactly, it can’t! So what happens is that as you open your mouth, the condyle slides forward and… CLICK! It pops back into the disc and continues its range of motion forward as it normally would, now held by the disc. But then when you close your mouth, the condyle and disc slide back until… CLICK! The condyle pops out of its nook and back into its unnatural state outside of the disc. I’ll link a video at the bottom of the article that animates this. When your joint is able to pop back into its normal operating position, it’s called reduction. So this is called Disc Displacement With Reduction.

For most people, this will not get worse. However in some cases, the articular disc can be pulled so far in front of the condyle that it folds up or gets stuck, and reduction no longer occurs (and the clicking goes away). This will result in a closed lock and is called Disc Displacement Without Reduction. DDwoR can be extremely painful and uncomfortable, and is something I myself still deal with. This condition is very hard to “cure” (return back to the anatomically correct position), but luckily most people find the pain mostly goes away and get most of their range of motion back with proper lifestyle changes and exercises. I for example have gone from being able to fit a finger into my mouth, to now being mostly pain free and able to eat normally ish. If you’re interested in a more detailed article about this topic, sign up for the mailing list and I’ll let you know when it comes out.

Another thing that often happens with disc displacement (with or without reduction) is the emergence of pain. Because of the articular disc shape, when the condyle isn’t sitting within the concave area of the disc, it’s actually being pushed by the thicker parts of the disc. Specifically, the condyle gets pushed backwards. And if you remember, there is highly nervous retrodiscal tissue there, which when compressed can cause a lot of pain.

But why would the articular disc be displaced in the first place? The culprit… the lateral pterygoid muscle.

Once again take a look at the diagram and find the lateral pterygoid muscle. Remember that it has 2 heads, one that attaches to the articular disc, and the other to the mandible (lower jaw). These heads actually activate opposite to each other, meaning when one tenses the other relaxes (kind of like the bicep and tricep). The lower lateral pterygoid’s job is to pull your mandible forward when you open your mouth. So when you open it tenses. The upper head of the lateral pterygoid’s job is to prevent your disc from sliding too far back when you close your mouth. So when you close your mouth it tenses.

This upper or “superior” lateral pterygoid muscle is what normally causes disc displacement. Because it is directly attached to the articular disc, think about what happens when that muscle tenses more than it should. For example, if you are a habitual clencher, or have improper jaw posture, you’ll constantly be contracting and pulling the disc forward. This can put you into a cycle - the more you clench, the stronger the muscles; the stronger the muscles, the harder the muscle contractions. Additionally, you’ll form muscle spasms (known as muscle knots) which can in of themselves be very painful and can contribute to the tension on the disc.

Note that disc displacement can also happen due to trauma.

The reason that your disc displacement doesn’t simply go away even when you relax your lateral pterygoid is partly because of the lack of elasticity in the TMJ ligaments. As I mentioned before, there is a network of ligaments in the joint, many of which attach the articular disc to the surrounding bones and tissues. Once these ligaments are damaged or stretched past a certain point, they may not be able to spring back to their original length, resulting in a new passively stable position. Additionally if there is inflammation, adhesions can form between the disc and surrounding tissue, once more limiting its movement.

Something a little different… Crepitus

You may be reading the explanation above and feel like it doesn’t explain the sounds coming from your own jaw. The majority of the time, noises are attributed to disc displacement. However if your TMJ sounds more like “creaking” and “crackling” rather than clicking or popping, then you might have crepitus.

In the simplest terms, crepitus is a symptom of later stage degeneration of the TMJ. This can occur with or without disc displacement being an earlier symptom. The main cause for crepitus is years of significant pressure on the jaw joint, or trauma. Remember how a healthy jaw has synovial fluid between the bony parts and the articular disc? In cases where joint deterioration has occurred, it is often seen that there is no space between the TMJ tissues. In fact the articular disc, or the ligaments that connect it to surrounding tissues, is torn/deteriorated to the point where you’ll have bone on bone contact. It’s this bone on bone contact that fails to absorb loads and reduce friction, therefore leading to bone degradation. All of this extra friction is what leads to the sounds you hear with crepitus.

How can I prevent and treat these things?

Now that we know why we hear TMJ sounds, we can understand the methods we can use to avoid them. Let me make it clear though that I am not a medical professional, and even if I was, TMJ Disorder treatment theory is not at the level where there is a one size fits all solution. What I explain below is simply to help you understand what and why certain treatment methods are used, in hopes that you’re able to find any that will work for you.

When it comes to disc displacement WITH reduction (clicking/popping), there are several interventions that can help. A common one is physical therapy. The theory is that by working on with the surrounding muscles, correct anatomical position can be achieved. For example, there are exercises that can help relax chronic muscle spasms in the lateral pterygoid (check out the myTMJ Exercises tab for examples). There also may be muscle spasms in other muscles that increase tension and therefore clenching. Or there may be imbalances that can be worked on by symmetry exercises.

Another big (and free) option is to really look into postural and habitual changes. For example, the resting position of the TMJ is with the mouth slightly open, the lips together, and the teeth not in contact. This is unlike the closed-pack position (used to help the joint deal with stronger forces) which has the teeth clenched together. Additionally the tongue should be resting on the roof of your mouth. Neck posture may also be a factor, since there is a hyoid muscle under your chin that can pull your jaw backward (and out of a minimally displaced disc) if your neck is forward for too long.

Apart from extreme surgical intervention, these are also often the best options for crepitus; the hope being that over a long period of decreased joint pressure, the disc can heal and reform, and continue preventing bone on bone contact.

There is also splint therapy to consider, in which a custom dental appliance is fitted to reduce joint compression with slight bite adjustment. It’s worth being cautious here though, since there is a lot of variance in doctor skill and care when making these splints. There are too many horror stories to ignore - and there is no one size fits all solution. So it’s important to talk to your doctor and make sure they’re not just rinsing you for money (splints are quite expensive).

When it comes to disc displacement WITHOUT reduction, it is believed that once the disc has been displaced that much, there is certain ligament damage that won’t let the disc go back to its healthy position without surgical intervention (in which the ligament is shortened and stitched up. However the current treatment philosophy also follows trying the least risky/costly techniques first. And therefore you will likely again be led to PT, in which they try to help the TMJ adapt to the new position. And the thing is that this actually has a very high success rate of improving quality of life (increasing range of motion and reducing pain). That’s because the articular disc is a very special soft tissue that can easily reform based on the surrounding pressures. So over time, it will in a way, shrink and get itself out of the way. However in this scenario, it is important to realize the joint will no longer have a disc to ride on, and will instead be riding on stretched ligament. This increases the sensitivity of the joint to overload, so it’s critical to implement measures to achieve a healthy bite, reduce clenching at all costs, and eat as little hard/chewy foods as possible. Otherwise you risk tearing the ligament completely over time, which will fully guarantee bone on bone contact and later arthritis.

If you found this article interesting or informative, consider following us on instagram @mytmjrelief