The Science Behind TMJ Muscle Pain and Relief

The TMJD Basics

Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) Disorders are a very very wide umbrella term to cover all dysfunction of the TMJ, surrounding muscles and ligaments. And of course, the wider the umbrella, the harder it becomes to tell you what the causes for TMDs are. But generally, the most common are from bad posture (whether its mouth-breathing during sleep, forward head position, improper tongue positioning, and a million other things), trauma, or overuse (think always clenching or grinding your jaw).

Sometimes, TMJ Disorders are painless (like when people's jaws click and they think it's normal), but other times they can be extremely painful. And the origin of this pain is nearly impossible to place. The fact is that some with a nearly ruined joint walk around completely pain free, while others with perfect TMJ health can't think of anything but the stabbing pain on their face.

But from what's out there right now (honestly isn't much), it's likely that the majority of TMD origins and pain is muscular in nature. I can't tell you your origins without a deep knowledge of your circumstances, but a way to tell if you have muscle pain is by pressing everywhere around the jaw muscles and temples. If any spot hurts or feels bumpy, it's likely a muscle spasm. On the other hand, if the majority of your pain comes in during joint motion (opening and closing), it's more likely pain from joint damage.

What is TMJ Muscle Pain

There are 2 kinds of muscle pain that apply to your TMD. Soreness, and Muscle Spasms (Muscle Knots, Trigger Points).

Soreness is more generalized pain, and as with any other muscle group, happens from overwork. For example, it's not uncommon for a person with TMJ Disorder to also have bruxism (nighttime clenching and grinding). Whether it's the cause of effect is unknown. But regardless, the constant tension can cause microscopic damage to muscle tissue, leading to inflammation and pain. It's actually a viscous cycle, because as the muscles grow in strength, clenching forces become higher, which causes even more damage to muscles, teeth, and the jaw joint. But be careful, because often times those same causes can create this second kind of pain which may be the real culprit.

Muscle spasms/knots on the other hand are localized points of sharp pain located in a tight band of muscle that may refer (spread) pain to other parts of the body. The crazy thing though, is that there is practically ZERO scientific understanding as to why they exist, and how they're treated. Why? Because it's difficult to do reproduceable science when dealing with something as subjective as pain. But there are a couple popular theories that are debated.

I won't get heavy on the molecules and proteins involved in the biological mechanisms of the theories, but the most popular one today that is taught to physical therapists and massage therapists is this: that essentially, muscle knots are sort of like mini cramps. In other words, it's an "energy crisis" causes by lack of oxygen and therefore energy to reverse a muscle contraction. When this happens across many muscle fibers in an area, this is where you get that painful bump on the muscle that can further compress blood vessels and prevent the reentry of oxygen into the site, creating a sort of "stable" state of hypoxic tension.

It appears to be that people with TMJ Disorders are extremely prone to developing these muscle spasms. As I mentioned, there is the angle of overuse from something like clenching or grinding, which has been shown to increase risk of developing spasms. But there's also the effects of muscle imbalances. For example, if a patient has a disc displacement on one side, the jaw is sort of sitting "crooked" where one side has less space in the joint cavity than the other. That patient will then develop tension on the opposite side of their disc displacement as a compensation, and therefore increase likelihood of muscle pain. The jaw is a complex system with many muscles at play, so such imbalances and compensations can happen in any dimension.

Relieving TMJ Muscle Pain

In cases where the scientific cause for pain is unknown, it's just as hard to figure out repeatable methods for pain relief. But humanity has been dealing with muscle pain for hundreds of thousands of years, and some of the methods we've developed are starting to be understood.

For soreness, because inflammation is the culprit, we can use NSAIDs (non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) like aspirin, ibuprofen, or naproxen. Technically, ice can help reduce pain from soreness too, but there's a big catch. It's been shown that when muscles are tensed for too long, they are much more likely to develop muscle spasms. It's not a good idea to apply cold, which restricts blood flow and stiffen muscle tissue, to an area that already has restricted blood flow and is too tense. Better thing to do is apply a heating pad, because heat receptors have been shown to take priority over some pain signals, making it act like sort of a pain signal blocker.

As for muscle spasms, it's been shown that pressure and heat are effective in releasing the tension and pain. This actually follows pretty well from the theory I discussed earlier. If a lack of energy is the thing that causes the muscle knot, then increasing blood flow should increase oxygen flow and therefore energy, allowing the muscle fibers to exit the state of contraction. Heat works to dilate blood vessels to maintain homeostasis, which increases blood flow. Pressure (massage) can also increase blood flow by decompressing blood vessels and pushing new oxygenated blood to the site. But pressure actually has been shown to relax muscle tissue through other mechanisms as well.

For example, there is a sensory receptor called the Golgi Tendon Organ that's attached to tendons. Its purpose is to sense when the muscle is overstretched (by sensing tension in the tendon) and force muscle relaxation. You can imagine the point of this reflex is to prevent damage to the tendon when it senses over tension. Massaging can trick this reflex by putting pressure on muscles, which puts tension on the tendon, and forces the brain to relax the muscle.

Final Notes

The weird thing though, is that you'd expect the pain to go away when you press on the muscle. After all, you're restoring blood flow right? Well for some reasons, when it comes to muscle knots, the pain gets SO much worse when pressed. This is why I recommend to COMBINE the massage with heat. As we stated before, heat acts like a pain blocker, which makes the pressure you need to apply to heal a lot more bearable.

It's important to note that the best thing for your TMJD is to address the root cause that's causing the muscle pain. Whether you do that through physical therapy, splint therapy, surgery, etc. (I wrote this guide if you're interested). But trust me, I understand that pain is pain, and if there's something you can quickly do to relieve it, you should.

If you don't know where to start, visit myTMJ Exercises for a solid list of massages and exercises that can work wonders on that pain of yours.

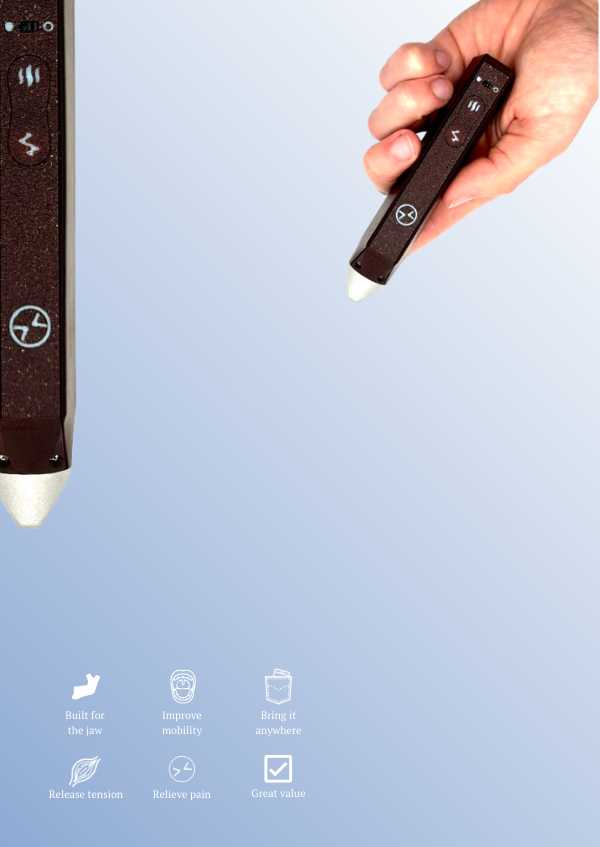

I created myTMJ Pen because for me, when I woke up in the morning with a locked jaw because of muscle tension in the lateral pterygoid, I needed a quick way to unlock it so I could brush my teeth and get to class. When at the end of the day my face was full of stabbing knots, I needed a quick way to relieve it so I could get to sleep on time. And for some reason, I couldn't find a device that combined heat with a tip that lets you put pressure on the muscle tissue. Plus I added vibration as an additional source of pain blocking. Here's a link if you're interested.